(1775 - 1851)

|

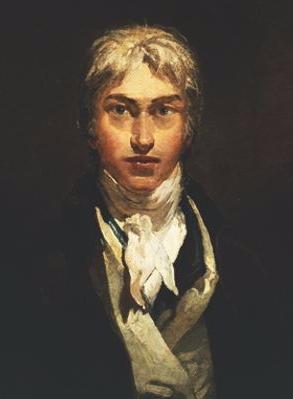

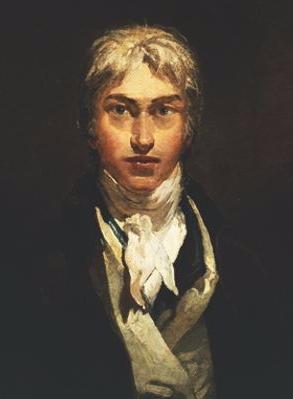

Joseph Mallord William Turner

(1775 - 1851) |

Turner's vast output of watercolours and oil paintings was in essence a record of a journey in which he started, as a young man, with an assured grasp of form and a dazzling technical competence in the handling of his medium and steadily worked his way towards a final grasp of the phenomenon of light- light which both reveals and destroys form, robs it of its won colour and bestows on it an iridescence that belongs to itself.

In the course of that journey he had been afraid

of nothing. He could tackle nature in any of her moods from the savagery

of a storm in the high Alps to the tranquility of Mediterranean sunset.

If, therefore, one is to choose a single example

out of this enormous variety of subjects in this long progress from form

to light, one must surely settle on a comparatively late one. And since,

despite his mastery of the subtlest inflections of oil painting, it was

in the medium of watercolour that his most brilliant interpretations of

light were achieved, one of those evanescent sketches of his maturity -

executed, certainly after 1835 - in which form is still there but is almost

eaten away by the light, will best serve to indicate his genius.

Because of all artists he was the most sensitive to subtle inflections in the intensities and the gradations of colour, no reproduction, however accurate, can quite do justice to his vision. The reader must therefore be prepared, in looking at this impression of the Rigi at sunset with the lake of Lucerne at its base, to reinforce Turner's vision with his own.

The watercolour is one of a series made by Turner during a visit to Switzerland in 1841. The scene is hardly sensational in its own right, but Turner must have felt impelled, as the sun sank behind the mountains, giving way to deepening twilight and, afterwards, to a moonlit night, to record with the utmost accuracy each passing phase of the changing light.

Yet accuracy is hardly the quality that we most aware of in the presence of Turner's best water-colours. They may be based on acute observation yet they achieve a lyrical quality that one does not associate with realism. In this example the last rays of the sun have spread a rose-colored veil across the upper slopes of the mountain. At its foot, level lines of blue mist spread themselves across the calmness of the lake, and the wooded slopes that come down to its edge are almost lost in the deepening twilight. The sharp accents of three boats break the surface of the water and one of them in the distance emits a trail of smoke that drifts upward into the mist. In the far distance one feels rather than sees the ranges of the high Alps.

From a purely technical point of view, the gradations

in the luminous sky from blue to the palest pink are the work of

a virtuoso, as anyone who has attempted such effects in watercolours will

known. Yet just as Turner makes one forget his realism, so also does he

conceal his virtuosity. It is as though he were identifying with the sunset

rather than describing it.

| Return to Artists' Eyes | Return to Oxford Eye Page |