Glaucoma

The term glaucoma goes back to hippocratic times. Its meaning is disputed; generally accepted to signify greenish -- like the colour of sea water -- Hirschberg has shown that it is much more likely to mean bluish. It would appear that in Hippocratic writings hypochyma and glaucosis were synonyms, and both vaguely referred to cataract. It is only with later Greek writers that a distinction was made between the two, glaucoma becoming the incurable condition as opposed to hypochyma which was curable, though not always so. Glaucoma which came also to stand for an affection of the lens itself, as opposed to cataract, which was a perverted humour in front of the lens. It is not at all unlikely that the term was applied indiscriminately to all blindness not considered as cataract and in which the pupil changed its colour. Absolute glaucoma with its "green cataract", as well as pupillary exudates, were probably included. Whatever else it may have stood for, it certainly did not stand for chronic glaucoma of today, for in this, as well as in the bulk of acute glaucoma, the discoloration of the pupil is not a striking feature. In any case it would only be the terminal stage of chronic glaucoma that would be recognized and this no doubt passed as amblyopia, amaurosis or, in later day as suffusio nigra or gutta serena.Glaucoma, in antiquity, therefore hardly stood for any definite entity. But the term created a problem in pathology when Brisseau showed that cataract was a disorder of the lens itself. Some, like Maître-Jan were content to let both diseases reside in the lens; others, like Brisseau, monopolized the lens for cataract and satisfied themselves that glaucoma was an affection of the vitreous, a view that led to much anatomical work to show what exactly the changes in the vitreous were. Vitreous fluidity, vitreous floaters and all sorts of vitreous abnormalities were brought forward as evidence for that view, and the discussions on the subject still persisted towards the middle of the last century. In these discussions other tissues were incriminated. Mackenzie, amongst others, blamed varicosity of the choroid.

All these discussions were of necessity futile, for they centred round a word rather than round a pathological entity. The essential feature of glaucoma - hypertension - was not not generally recognized till about 1840, and even so, recognition only extended to acute glaucoma and absolute glaucoma. It was in fact a new entity that was being built up -- a disease in which the cardinal sign was increased tension, and in which the name glaucoma had come to be a meaningless label. The problem was no longer why the pupil was discoloured but why the tension was increased.

The first clear recognition of absolute glaucoma came with Rikchard Banister in 1622. Discussing the differential diagnosis between curable cataract and incurable gutta serena in which "the humour settled in the hollow nerves, be growne to any solid or hard substance, it is not possible to cured" he gives foure wayes," one which is "if one feele the Eye by rubbing upon the Eie-lids, that the Eye be growne more solid and hard than naturally it should be." The three other tests were no different from those in common use at that time for determining the curability of cataract. Banister's tetrad -- long duration, no perception of light, increased hardness and no dilatation of the pupil on bandaging the sound eye - is a passable account of absolute glaucoma. His teaching, however failed to attract any attention. Hardness of the eye is next found in the literature a hundred and twenty years later, in J.Z.Platner, with nothing like Banister's completeness. At the beginning of the 19th century it was rediscovered; it appears in a number of books at about 1820, and in Mackenzie's classical text-book of 1830 it is given definitely in the differential diagnosis between glaucomatous amaurosis and cataract

Acute glaucoma, though not under that name, has a more considerable antiquity. The Arabian Sams-ad-din recognized it as a distinct entity in the amorphous mass of ophthalmias. He described under "Migraine of the eye, also known as Headache of the pupil" a condition in which there is a deep-seated pain in the eye associated with hemicrania and dullness of the humours; the condition is sometimes followed by cataract and dilatation of the pupil; if it becomes chronic, tenseness of the eye and poor vision supervene. This conception of a distinct disease does not, however, seem to have prospered. Though tentative attempts at the recognition of acute glaucoma were made by several writers in the 18th century, it is not till 1813 that really convincing description occurs -- an account by Beer. A form of iritis is differentiated from the other varieties by its distinctive symptoms and in that it ends in blindness, a greenish hue (glaucoma), a dilated pupil and cataract -- a tolerable description of the terminal stage of neglected acute glaucoma, even though the cardinal sign of hypertension is mission. In his ambitious attempt to describe eye conditions on a basis of causation, Beer named this acute condition as iritis of gouty origin. Rainbow colours and hardness of the eye in a condition termed glaucoma appear five years later in a description by Demours. Subsequent publication speak of arthritic iris (and ophthalmitis), as well as glaucoma, in describing conditions which appear to have been the same, apart from the presence of the greenish pupil reflex in the latter. The first to recognized that these two conditions were identical was Sir William Lawrence; he considered glaucoma " to be merely a chronic form of the same inflammation as the arthritic inflammation affecting the posterior coats of the eye". It was also he who introduced the term of acute glaucoma (1829).

Lawrence did not link up acute glaucoma with what we now call chronic glaucoma, but with what now passes as absolute glaucoma -- their link being not hypertension but the greenish discoloration. It was only when the ophthalmoscope had revealed cupping of the disc that hypertension as the essential feature of glaucoma was finally realized. Even so, von Graefe in 1857 missed chronic glaucoma; he speaks of the acute, chronic (ie, absolute), and secondary glaucoma and of amaurosis with excavation of the disc. Not till Donders recognized this last group as glaucoma simplex was the unifying conception achieved, a teaching that gained greatly from Bowman's simple numerical notation in recording the findings of digital measurement of tension.

When the older writers spoke of the incurablitiy of glaucoma, they were right not only by their standards but by our own, for the condition they discussed was absolute glaucoma. Acute glaucoma, in contra-distinction to chronic glaucoma, only emerged after 1830, and that too must have been incurable, for only very severe attacks would be recognized as glaucoma and the treatment would not improve matters, for it consisted of the same as for other forms of iritis. Till 1857, when von Graefe introduced iridectomy for acute glaucoma, the diagnosis was indeed tantamount to a sentence of blindness, for even relief from miotic was unknown till about 1875. Not infrequently matters must have been made worse by treatment for belladonna was used.

Iridectomy for acute glaucoma received the same mixed reception as every great innovation, and not altogether without reason. The rationale of the operation was then rather vague. Von Graefe was led to the operation in the belief that staphylomata of the cornea regressed after iridectomy, presumably because of lowering of tension. To not a few surgeons operative interference meant adding trauma to an already markedly diseased eye. Feeling ran high and the discussions in the subject were by no means free from acrimonious tendencies. When the collective experience of the profession clearly established the value of the operation, discussion ranged as to its mode of action. To some the favourable results were caused by a filtering scar induced by the iridectomy, and this led to the various sclerectomies having filtration as their object.

The cause of the increased intra-ocular pressure was seen by von Graefe in a serious choroiditis increasing the watery contents of the eye. To Donders it was due to an increased secretion of the choroid. Stellwag regarded it as the result of increased pressure in the ocular circulation, whilst Priestley Smith stressed faulty excretion rather than secretion, the immediate cause being abnormalities in the angle of the anterior chamber.

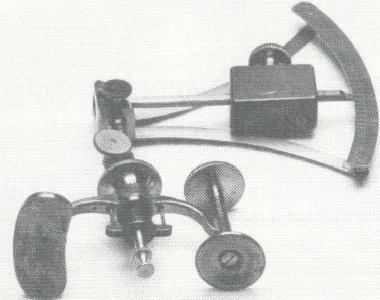

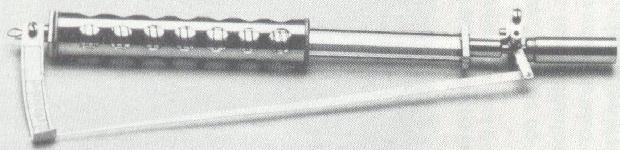

Tonometers through the ages

Donders' tonometer (1868)

von Graefe's tonometer (1862)

Snellen's tonometer (1900)

Seeuwen's tonometer (1901)